Alternatives to animal testing are the future — it’s time that journals, funders and scientists embrace them

Summary

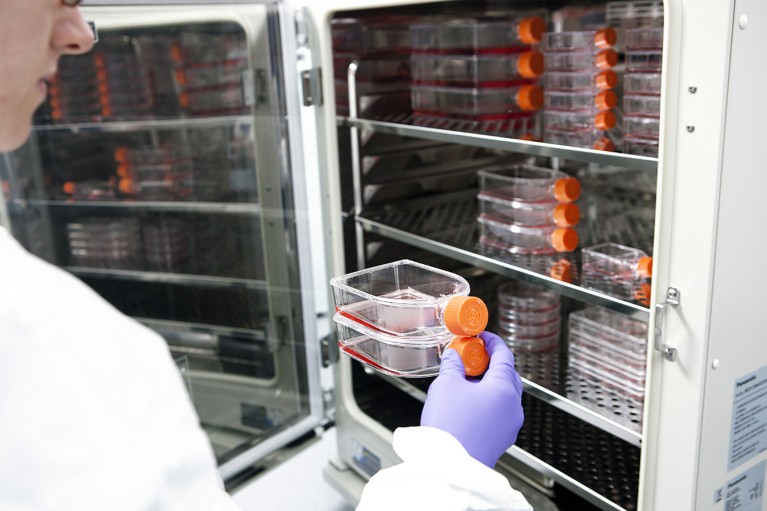

Biomedical researchers are increasingly using novel alternative methods (NAMs) — such as organoids, multicellular in vitro systems, in chemico assays and in silico models — as replacements for animal testing. NAMs, often built from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) or patient-derived tissues, can better capture human genetic variability, reduce ethical concerns, lower costs and speed drug discovery. Despite growing regulatory support (for example from the FDA and NIH) and clear potential for ‘clinical trials in a dish’ (CTIDs), early adopters face pushback from reviewers, journals and funders who still favour animal validation. The authors call for systemic changes in publishing, funding and regulation so researchers using NAMs are supported rather than penalised.

Key Points

- NAMs include organoids, tumour spheroids, iPS-derived tissues, in chemico assays and in silico models that mimic human biology more closely than many animal models.

- Organoids and 3D cultures enable ‘trials in a dish’ to test therapies across panels of patient-derived samples, which is useful for rare genetic diseases and personalised approaches.

- NAMs can capture human genetic diversity and microenvironmental factors, improving prediction of human efficacy and toxicity and reducing the high failure rate in clinical trials.

- Regulatory bodies are beginning to support NAMs — examples include FDA moves on monoclonal-antibody testing and NIH investment in organoid infrastructure.

- Researchers still face barriers: peer reviewers and funders often ask for animal validation, disadvantaging NAM-led studies and early-career scientists using alternatives.

- At scale, NAMs tend to cost less than animal studies and could enable more inclusive testing, benefiting under-represented populations and low- and middle-income countries.

- The authors urge journals, funders and regulators to adapt policies and incentives so NAM development and adoption accelerate.

Content summary

NAMs are gaining traction because they reduce ethical issues and offer more human-relevant data early in the drug-development pipeline. iPS cells and organoids allow creation of human tissue models from patient samples; engineered extracellular matrices and microfluidic systems can recreate tumour microenvironments and circulatory dynamics. Computational tools and AI (for example AnimalGAN and QSAR models) help triage candidates before any in vivo work. CTIDs, using panels of organoids from many donors, could identify effective therapies, train AI models and speed personalised medicine. Despite demonstrated benefits and recent government initiatives, cultural and structural resistance remains in academia and funding systems.

The authors highlight that 86% of drug candidates fail in human trials, often because animal models do not predict human responses. NAMs offer a route to better translational success, lower costs and fairer, more inclusive research. To unlock this potential, the scientific ecosystem must stop automatically privileging animal data as the gold standard and change review, funding and publication practices to validate and reward NAM-based work.

Context and relevance

This piece sits at the intersection of drug discovery, ethics and research policy. It reflects a wider push by regulators and funders to modernise preclinical testing and reduce animal use, while pointing out the mismatch between rapid technological advances and slower institutional change. For researchers, funders and policy-makers, the article explains why NAMs matter now: they can improve predictivity, cut costs and broaden participation in research — but only if gatekeepers update expectations and incentives.

Why should I read this?

Short version: if you care about better, cheaper, fairer drug development (and who doesn’t?), this is worth your five minutes. The authors spell out how real human-based models are already outperforming old animal-first workflows and why journals and funders still slow things down. It’s a clear call to stop treating animal data as an automatic requirement and to start backing the tech that actually predicts human outcomes.