AI wins Imitation Game: Readers prefer Fanfic written by ChatGPT

Summary

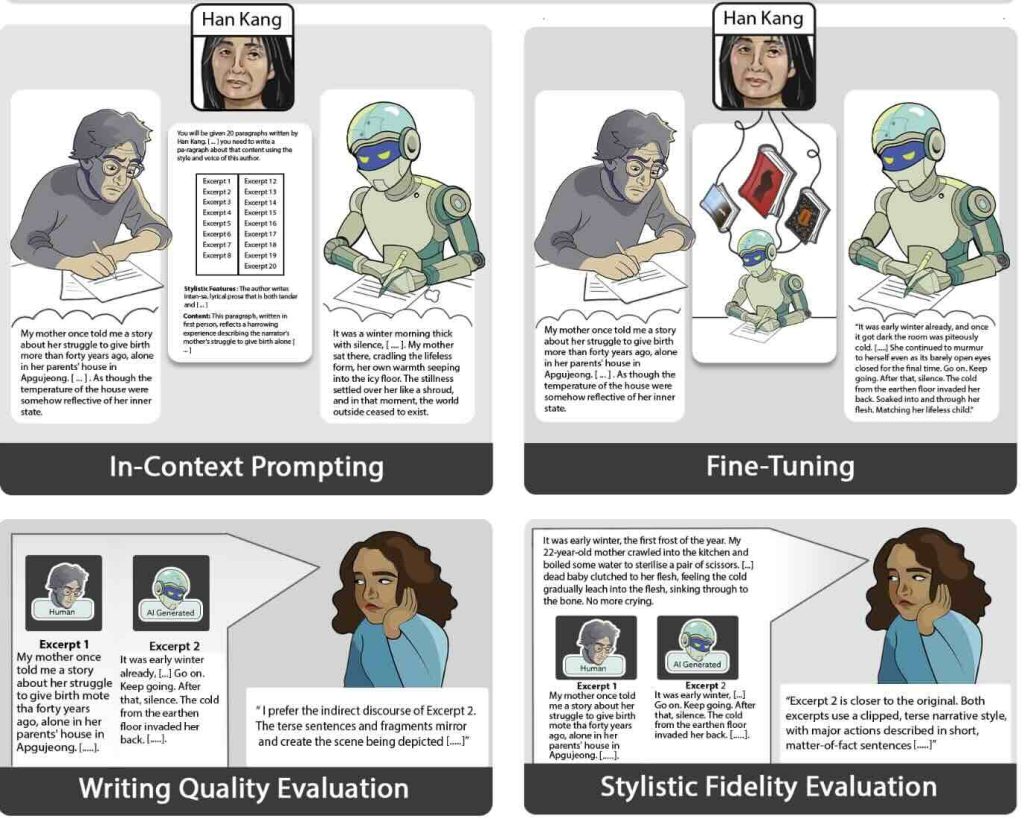

Researchers have found that large language models fine-tuned on the collected works of individual authors can produce short literary excerpts that readers (including expert MFA candidates) prefer over expert human-written imitations. A preprint titled “Readers Prefer Outputs of AI Trained on Copyrighted Books over Expert Human Writers” reports blind pairwise tests comparing 150 human imitation excerpts (written by MFA candidates) with 150 AI-generated excerpts. Initial in-context prompting was disfavoured, but after fine-tuning ChatGPT on an author’s complete works the preference flipped in favour of AI for stylistic fidelity and quality. The paper emphasises the low cost of fine-tuning (median estimate: $81 to produce a 100,000-word novel) and warns of significant market and legal implications for copyright and fair use.

Key Points

- The study compared 150 human-written imitations (MFA candidates) against 150 AI-generated excerpts modelled on 50 award-winning authors.

- Experts and lay readers initially preferred human imitations when AI used only in-context prompting; fine-tuning the model on an author’s complete works reversed that preference.

- Fine-tuned AI removed detectable stylistic quirks that readers dislike, boosting perceived stylistic fidelity and writing quality.

- Researchers estimate the median cost to fine-tune and generate a 100,000-word novel is about $81, versus roughly $25,000 to commission a professional writer.

- Authors and legal scholars argue this outcome strengthens claims that training on copyrighted works may not be fair use if the resulting models substitute for the market of original works.

- The paper arrives amid dozens of US copyright lawsuits (e.g. Bartz v. Anthropic, Kadrey v. Meta) challenging AI firms’ use of copyrighted material for training.

Context and Relevance

This research directly bears on ongoing legal debates about whether scraping copyrighted books to train generative AI is fair use. If fine-tuned models can produce market-competitive works at tiny cost, courts must consider not just verbatim copying but whether training substitutes for authors’ markets. The finding also matters to publishers, authors, platform owners and policymakers concerned with AI-driven disruption in creative industries. It intersects with broader trends: rapid advances in fine-tuning, falling generation costs, and a rising wave of copyright litigation aimed at AI developers.

Why should I read this?

Short answer: because this paper shows AI isn’t just clumsy mimicry anymore — it can out-style human imitators once properly trained. If you care about books, IP law, publishing economics or how AI will change creative jobs, this is the neat, worrying evidence you need without wading through the legalese.

Author style

Punchy: the research packs a headline-friendly punch — low-cost, high-fidelity AI that can beat expert human imitators. If you worry about where writers, publishers and copyright law go next, the paper’s implications are urgent and worth digging into.