Integrator dynamics in the cortico-basal ganglia loop for flexible motor timing

Article meta

Article Date: 19 November 2025

Source URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09778-2

Image:

Summary

This Nature paper dissects how the frontal premotor cortex (anterolateral motor cortex, ALM) and the striatum cooperate to produce flexible, seconds-scale motor timing. Using a high-throughput lick-timing task in head-fixed mice, the authors combine large-scale electrophysiology across ALM and ventrolateral striatum (VLS) with transient, calibrated optogenetic perturbations and computational modelling.

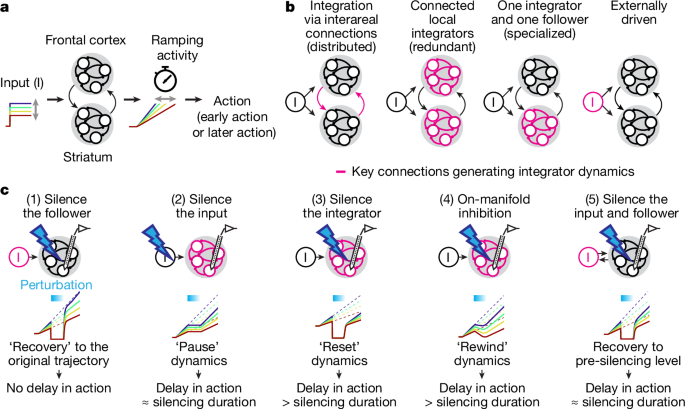

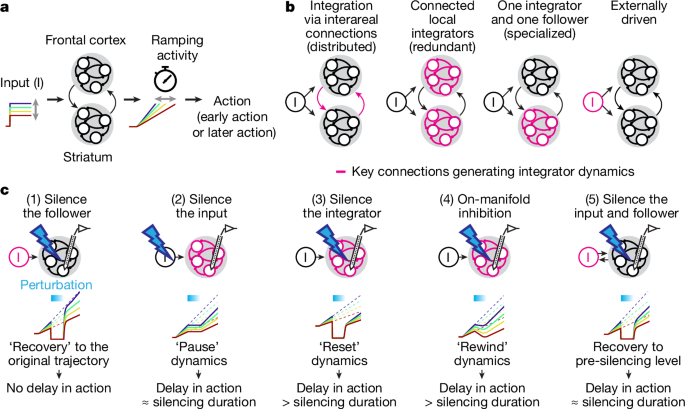

Key findings: many neurons in both ALM and striatum show temporally scaled ramping dynamics that predict when an animal will act. Trial-history information is encoded tonically in ALM before a cue and is integrated after cue onset to set ramp slope. Critically, transient ALM silencing produces a near-state-independent delay (a “pause” of the timer), whereas transient inhibition of D1 striatal projection neurons produces a larger, state-dependent delay and can “rewind” the timer. The data and models support a circuit in which a subcortical integrator (striatum and/or downstream subcortical loop) accumulates cortical inputs to generate timing dynamics, with ALM acting both as input and a follower of that integrator.

Key Points

- Mice performed a flexible lick-timing task; behaviour depended on recent trial history when delays varied.

- ALM and striatum populations exhibit temporally scaled ramping activity whose speed predicts lick timing on single trials.

- Many ALM neurons hold trial-history signals before the cue; projecting those into a trial-history mode explains subsequent ramp slope via temporal integration.

- Transient, calibrated ALM silencing during the delay produced a timing shift approximately equal to the silencing duration — interpreted as a pause of the timer with rapid recovery of ALM and striatal dynamics.

- Transient inhibition of D1-SPNs in ventrolateral striatum caused a stronger, state-dependent shift (a “rewind”) and increased no-lick trials, indicating integration of the perturbation into the timer state.

- Simultaneous recordings plus k‑NN decoding showed tight single-trial coupling between ALM and striatum timing representations.

- Network models (feedforward and recurrent variants) best matched the data when the striatum or a subcortical loop served as the integrator and ALM provided on-manifold (timing) and off-manifold (excitatory drive) inputs.

Content summary

The authors built a flexible lick-timing paradigm allowing many perturbations per session. They recorded thousands of ALM and striatal neurons across dozens of mice. Dimensionality-reduction revealed three task modes (cue, middle, ramp); the latter two scale with lick time. Trial-history information encoded in ALM before the cue predicts ramp slope and upcoming lick time. Optogenetic silencing was carefully calibrated to avoid rebound artefacts.

During calibrated bilateral ALM silencing (0.6 s), ALM ramp activity collapsed but recovered quickly after stimulation; the behavioural delay matched the silencing duration — consistent with pausing integration. Striatal activity decreased but retained rank order and timing information, suggesting the integrator is outside ALM. By contrast, inhibiting VLS D1-SPNs produced a gradual decay of timing dynamics and larger, state-dependent behavioural effects; this was modelled as rewinding the integrator state. The authors interpret these divergent perturbation effects as evidence that striatum (or a striatum–SNr–thalamus loop) implements the integrator, while ALM supplies trial-history and excitatory inputs and follows the integrator state.

Context and relevance

This study speaks directly to longstanding debates about where and how the brain times actions over seconds. Previous work showed ramping correlates across cortex and basal ganglia; here, transient, multi-site perturbations plus simultaneous recordings separate computational roles. The result — cortical inputs set initial conditions and supply drive, while a subcortical integrator accumulates those signals — offers a parsimonious mechanism for flexible motor timing and links to evidence-accumulation paradigms in decision neuroscience.

Why should I read this?

Because it neatly answers a gnarly question: are cortical ramps the timer or just the messenger? Short answer — both. The paper uses neat tricks (many trials, calibrated brief perturbations, simultaneous recordings) to tease apart pause vs rewind effects — stuff other papers couldn’t settle. If you care about timing, basal ganglia function, or how to combine perturbations with population recordings, this is worth five minutes of your time (or a proper read if you’re implementing experiments or models).

Author style

Punchy and decisive. The authors make clear, testable claims and back them with dense electrophysiological datasets and targeted causal manipulations. The interpretation — a subcortical integrator shaped by cortical initial conditions — is amplified as both mechanistically plausible and broadly relevant across motor and cognitive timing tasks.