Structural basis of regulated N-glycosylation at the secretory translocon

Summary

This Nature study uses selective ribosome profiling and single-particle cryo-EM to reveal how nascent GRP94 is cotranslationally shielded from inappropriate N-glycosylation at the secretory translocon. The authors capture ribosome–SEC61–OST-A complexes bound to FKBP11 and CCDC134 and visualise a GRP94 translation intermediate whose N-terminal pre-N segment occupies the OST-A active site as a pseudo-substrate. CCDC134 binds a transient amphipathic helix in the nascent chain, stabilising a non-native conformation that tethers GRP94 to the translocon and helps form a lumenal vestibule that limits access by OST-B. Structural and cellular mutational data link this mechanism to regulated glycosylation, ER-associated degradation of hyperglycosylated GRP94, and defects in receptor maturation; loss of CCDC134 function is connected to disease phenotypes such as osteogenesis imperfecta.

Key Points

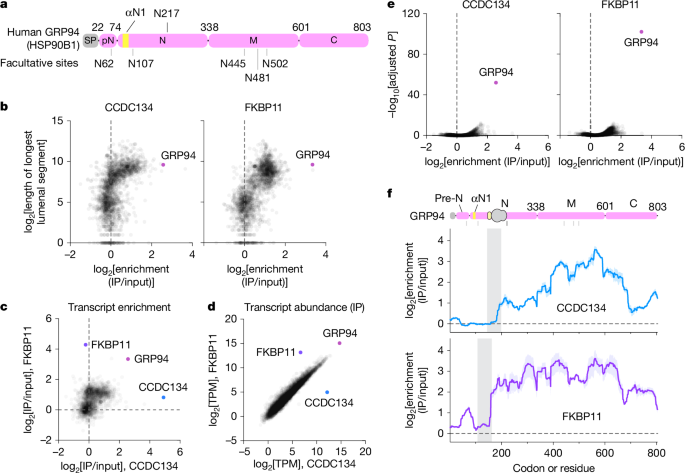

- Cryo-EM of native ribosome–translocon complexes shows nascent GRP94 residues 22–283 bound across OST-A, CCDC134 and FKBP11.

- The GRP94 pre-N segment acts as a pseudo-substrate that occludes the STT3A (OST-A) acceptor site and prevents cotranslational glycosylation of downstream facultative sites.

- CCDC134 recognises and stabilises a transient amphipathic helix (αN1) in nascent GRP94 via a conserved hydrophobic groove, tethering the polypeptide to the translocon.

- FKBP11 helps recruit CCDC134 to ribosome-associated translocons but is not absolutely required in all cell types; its role may be context-dependent.

- Translocon remodelling (TRAP movement, KCP2/DC2 positioning) creates a lumenal vestibule that shields the tethered nascent chain from OST-B acting in trans.

- Mutations in GRP94 pre-N, in STT3A or in CCDC134 perturb this regulatory interaction, causing GRP94 hyperglycosylation, ERAD and impaired surface expression of client receptors (eg IGF1R, LRP6, TLR4).

- Findings link substrate-driven translocon assembly and cotranslational quality control to congenital disorders of glycosylation and to diseases caused by CCDC134 loss-of-function.

Author’s take

Punchy and clear: this is a structural tour de force that explains how the translocon discriminates between sites that should — and should not — be glycosylated during translation. The work gives a concrete molecular mechanism for previously observed GRP94 hyperglycosylation and ties it to cell physiology and human disease.

Why should I read this

Short answer: because it actually shows you, in atomic detail, how a nascent protein can block its own glycosylation and how the ER builds a little protective pocket to stop the wrong sugars getting stuck on. If you care about protein biogenesis, ER quality control, congenital glycosylation disorders or receptor maturation, this paper saves you time by unpacking a complex cotranslational mechanism with crisp structural and functional evidence — and gives you testable mutants to play with.