Ancient DNA from Shimao city records kinship practices in Neolithic China

Article meta

Article Date: 26 November 2025

Article URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09799-x

Article Image: Figure 1

Summary

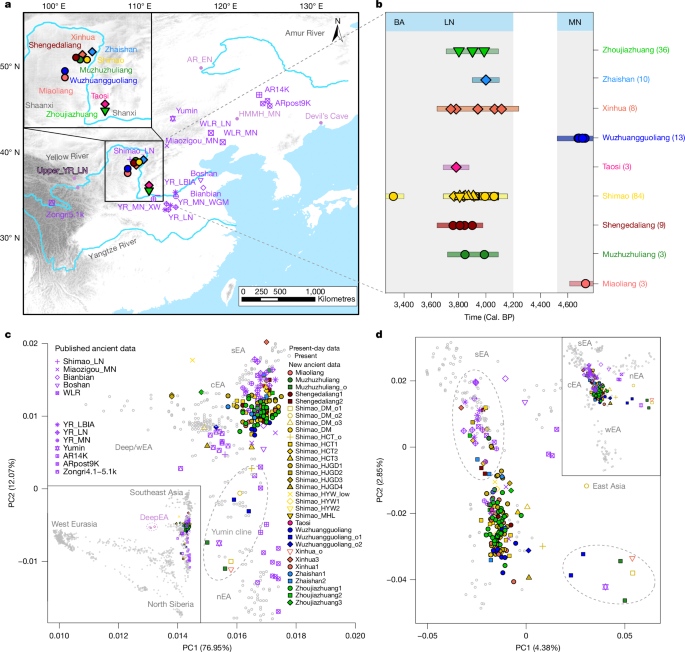

This study uses genome-wide ancient DNA from 169 individuals (144 analysed for population structure plus 25 close kin) excavated from Shimao city and nearby sites on the Loess Plateau to reconstruct ancestry, kinship and burial practices across the Middle to Late Neolithic and Bronze Age (roughly 4,800–3,200 cal. BP). The authors find strong genetic continuity between earlier Yangshao-associated populations (represented by Wuzhuangguoliang) and later Shimao inhabitants, intermittent influxes of a Yumin-related steppe/Inner Mongolia ancestry in some outliers, and occasional southern coastal ancestry in a few individuals. Dense kinship and IBD analyses reveal multi-generation pedigrees dominated by a patrilineal descent pattern (common Y haplogroup O3a2c among high-status males), evidence consistent with female exogamy, low incidence of close-kin mating overall, and contrasting sacrificial practices: male-dominated mass sacrifices at the East Gate versus predominantly female sacrifices accompanying elite burials.

Key Points

- Shimao populations show clear genetic continuity with local Yangshao-era ancestors (Wuzhuangguoliang), indicating local population persistence for ~1,000 years prior to city formation.

- A minority of individuals bear Yumin-related (Inner Mongolian/steppe) ancestry; such influence increased intermittently from the Middle to Late Neolithic without replacing local ancestry.

- Some Shimao outliers carry southern/coastal mainland or Taiwan-related ancestry, suggesting long-distance contacts tied to the northward spread of rice-farming-associated groups.

- Dense pedigree reconstruction (IBD, READ, lcMLkin, ancIBD) identifies extended pedigrees over two to four generations, with a dominant patrilineal signal among elite male tomb owners (shared Y haplogroup O3a2c) and diverse maternal lineages.

- Sacrificial customs differ by context: the Dongmen (East Gate) mass burials are male-biased (likely construction or public ritual sacrifices), while elite cemetery-associated sacrifices are predominantly female and usually unrelated to tomb owners, suggesting gendered and status-based ritual roles.

- Overall, the population maintained healthy diversity and avoided widespread close-kin mating; only a few individuals show long ROH consistent with recent parental relatedness.

- There is little evidence for substantial gene flow from distant West Eurasian or steppe sources into the main Shimao gene pool despite archaeological parallels, implying trade and cultural contact without major demographic replacement.

Context and relevance

This genome-scale survey is among the most detailed ancient-DNA datasets for an East Asian, state-like Neolithic urban centre. It directly links archaeological models of Shimao’s rise—urban planning, craft specialisation and hierarchical burial—to biological kinship and population history. The results inform broader debates on state emergence, mobility corridors between farming and herding economies across the Ordos–Loess Plateau corridor, and how ritual and lineage shaped early political power in northern China. For scholars of archaeogenetics, archaeology of early states and palaeodemography, the paper is a major dataset that situates Shimao within regional interaction networks while resolving local descent and marriage practices.

Author style

Punchy — the paper is written and presented as a decisive step: big sample, rigorous methods, clear takeaways. If you work on ancient social organisation or East Asian prehistory, this amplifies why kinship and burial data really matter; the genetic results back up and refine archaeological narratives rather than overturn them.

Why should I read this?

Quick and straight: if you care about how early complex societies organised families, inheritance and ritual, this study gives hard genetic answers. It shows that Shimao’s elites were largely patrilineal, that sacrifices were gendered depending on context, and that long-range trade/cultural links didn’t always mean mass immigration. We’ve cut the slog — read this to get the data-driven view of how lineage, marriage and ritual made an early Chinese city tick.

Limitations

The authors note limited sample sizes for some contexts (sacrificial pits, certain cemeteries), which reduces statistical power for population-wide sex-bias estimates and for definitively proving female exogamy; further sampling would refine demographic models and mating patterns.