Land-use change undermines the stability of avian functional diversity

Summary

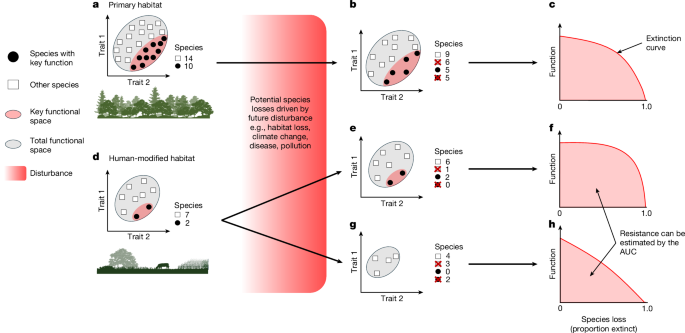

This Nature paper analyses how anthropogenic land-use change reshapes bird communities worldwide and, crucially, undermines the stability of the ecosystem functions they support. Using trait hypervolumes and extinction simulations, the authors show that while some human-modified habitats can retain overall trait richness, functional redundancy and resistance decline—especially in groups that provide seed dispersal and insect control. The work uses a global sample (3,696 species across 1,281 assemblages) and combines AVONET trait data with PREDICTS and other survey datasets to quantify functional diversity (FD), redundancy, vulnerability and resistance under realistic species-loss scenarios.

Key Points

- Global dataset: 3,696 bird species in 1,281 assemblages sampled across land-use gradients from pristine vegetation to urban areas.

- Functional diversity (FD) measured as probabilistic hypervolume (functional richness) generally declines in heavily modified land uses—most sharply in intensive cropland and urban landscapes.

- Functional redundancy initially rises slightly in lightly disturbed primary vegetation but falls markedly in intensive agriculture and urban areas, eroding the insurance effect against species loss.

- Frugivores (seed dispersers) and invertivores (insect predators) suffer the steepest declines in FD and redundancy, risking collapse of key ecosystem services.

- Simulated species-loss scenarios (trait- and rarity-based) show reduced functional resistance in human-modified habitats, meaning FD falls faster when species are removed.

- Lower measured functional vulnerability in disturbed assemblages (because sensitive species have already been filtered out) does not offset the loss of redundancy—disturbed assemblages are more fragile under further shocks.

- Well-developed secondary vegetation and lightly disturbed habitats can retain redundancy levels similar to pristine sites, highlighting restoration value.

Content summary

The authors combined global bird-survey data (primarily PREDICTS plus targeted studies) with AVONET morphological and dietary trait data. They reduced collinear morphometrics via sequential PCAs and constructed trait probability densities (TPDs) in a multi-dimensional trait space incorporating diet and four morphological axes (trophic, locomotory, dispersal and size). FD was measured as occupied trait hypervolume; redundancy as the average number of species per trait-space cell; vulnerability as the covariance between species redundancy and sensitivity scores; and resistance as the area under simulated extinction curves (and half-life alternative).

Across land-use types, heavy disturbance (cropland, intensive urban) consistently reduced FD and redundancy. Trophic analyses show dietary generalists and granivores often remain or even increase in disturbed landscapes, masking dramatic losses in frugivores and invertivores. Simulated extinctions—removing species in order of trait-based sensitivity or rarity—produced sharper FD declines in human-modified landscapes. Sensitivity analyses (climate-trait scores, probability-weighted loss, alternative intraspecific variance estimates) produced similar patterns, supporting the robustness of conclusions.

Context and relevance

This study reframes how we judge ecosystem resilience under land-use change. Traditional whole-assemblage FD metrics can give a false sense of retained function because gains in tolerant generalists obscure losses of functionally unique specialists. The finding that frugivores and insectivores are disproportionately affected links directly to risks for seed dispersal, forest regeneration and biological pest control. That has clear implications for agriculture, restoration, and climate-change adaptation: ecosystems that appear functionally intact may nonetheless lack the redundancy required to absorb further shocks.

The paper also connects to broader trends: biotic homogenisation, extinction filtering and the growing evidence of synergistic impacts of land-use and climate change. For managers and policymakers, the message is twofold: protect intact and recovering semi-natural habitat, and prioritise the functional roles (not just species counts) when planning landscape management and restoration.

Why should I read this?

Short version: because it explains why simply counting species or looking at average trait richness can fool you. Want to know whether an urban park or a restored patch will actually keep doing the ecological jobs we need (seed dispersal, pest control)? This paper tells you which bird groups matter, how land use chips away at the insurance built into diverse assemblages, and why some apparently “resilient” sites are actually primed for collapse if losses continue. It’s a neat, data-rich reality check — read it if you care about conservation outcomes, ecosystem services or landscape management.