Progressive coevolution of the yeast centromere and kinetochore

Article Date: 26 November 2025

Article URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09779-1

Article Image:

Summary

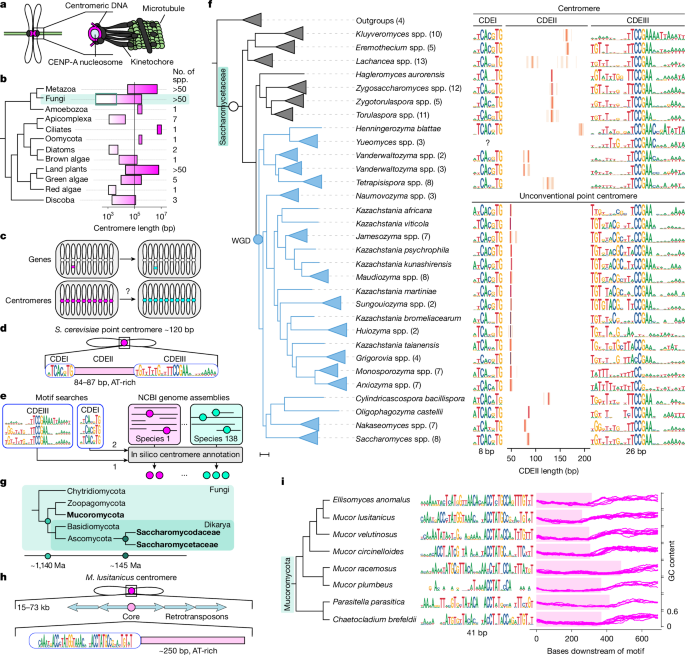

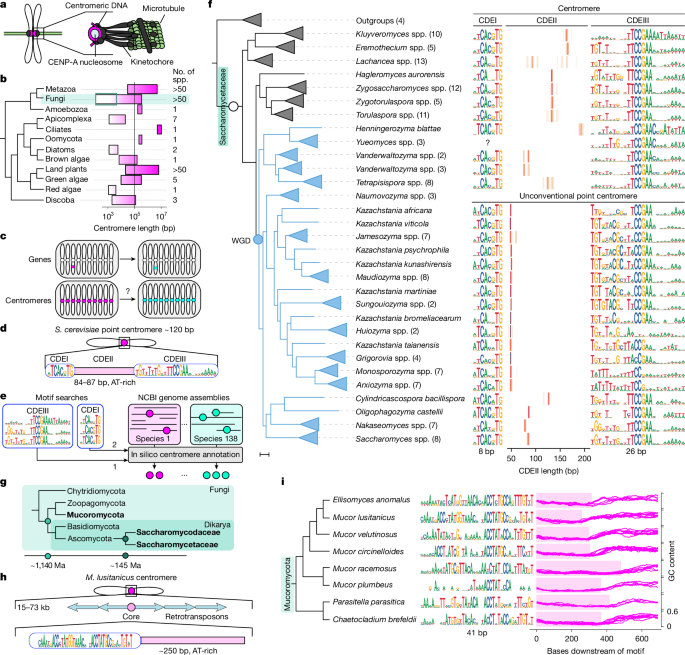

This Nature study maps centromere sequence diversity across budding yeasts and some early-diverging fungi, and shows that centromeres evolve progressively (one chromosome at a time) through a mix of drift, selection and sexual recombination. The authors developed an automated point-centromere annotation pipeline (PCAn), used it to build an atlas of point centromeres across 138 Saccharomycetaceae species and adapted it for Mucoromycota. They combine large-scale comparative genomics, population surveys in S. cerevisiae, simulations and plasmid-based functional assays to demonstrate that (1) centromere sequence features (notably the AT-rich CDEII length) vary extensively between species yet are consistent within genomes, (2) transitions often proceed via intermediate genomes carrying mixed centromere types, (3) full replacements require positive selection (or selection plus sex), and (4) changes in kinetochore proteins (for example Cbf1) can coevolve to favour particular centromere variants.

Key Points

- PCAn: a motif-based automated pipeline that annotated point centromeres in 138 Saccharomycetaceae genomes and was adapted to detect core centromeres in Mucoromycota.

- CDEII (AT-rich centromeric region) length varies nearly fourfold between species but is remarkably consistent within a genome.

- Centromere transitions are progressive — genomes can carry two centromere types simultaneously, indicating stepwise replacement rather than wholesale switching.

- Population data (1,493 S. cerevisiae strains) show ~9.5% of strains carry atypical CDEII variants; multiple distinct variants have arisen and spread through sex.

- Simulations indicate full genome-wide centromere replacement is unlikely under drift alone: selection (and sexual recombination) is needed to fix new variants.

- Most length expansions arise via microhomology-mediated insertions, plausibly from stalled replication forks or repair during meiosis.

- Kinetochore components (notably Cbf1) show episodic diversifying selection; experimental swaps of CBF1 alter which centromere variant is best retained, supporting coevolution.

- Transitions are constrained by the kinetochore interface — ~10 bp jumps in CDEII (roughly a DNA helical turn) preserve motif orientation and are better tolerated than smaller changes.

Content Summary

The authors produced a clade-wide atlas of motif-defined point centromeres by running PCAn across 138 Saccharomycetaceae species and validated predictions using synteny, known chromosome counts and targeted sequencing. They documented extensive interspecific variation in the two defining motifs (CDEI and CDEIII) and, especially, in CDEII length. Within individual genomes CDEII lengths cluster tightly, but across species the modal length shifts multiple times during ~114 Myr of evolution.

Comparative analyses revealed species with two distinct centromere length classes coexisting in the same genome — interpreted as transitional states. Forward simulations starting from a complete ancestral set show that random one-by-one changes cannot produce full replacement across all chromosomes under neutrality; positive selection for the new variant is required. Including sexual recombination in simulations increases the chance of fixation, matching empirical observations from natural S. cerevisiae populations where several independently arisen variants are shared across clades.

Functional plasmid retention assays across Jamesozyma and Saccharomyces species showed that longer-centromere variants can be neutral or advantageous depending on species background. Protein evolution analyses (aBSREL, contrast-FEL) and AlphaFold2 structural predictions implicate adaptive changes in Cbf1 that alter electrostatics near the DNA-binding/leucine-zipper region. Swapping CBF1 alleles into S. cerevisiae shifts preference for short versus long centromere plasmids, providing direct evidence of centromere–kinetochore coevolution.

Context and Relevance

Centromeres are essential yet among the fastest-evolving genomic elements. This work provides one of the clearest, data-rich demonstrations of how centromere DNA and kinetochore proteins can coevolve: initial neutral or nearly neutral centromere variants can spread through drift and sex, but fixation across all chromosomes typically requires selection, possibly following adaptive changes in kinetochore factors. The study links mechanistic mutational processes (microhomology-mediated insertions), population dynamics, and molecular coadaptation — relevant to researchers studying chromosome segregation, genome evolution, speciation, and centromere drive hypotheses.

PCAn and the accompanying datasets (Figshare, Zenodo) provide useful tools and resources for anyone mapping motif-defined centromeres in fungi and related clades, and the conceptual framework should be translatable to other eukaryotes where motif-like centromere elements exist (for example CENP-B boxes in mammals).

Why should I read this?

Quick version: if you care about how chromosomes stay put while DNA sequence around the centromere spins faster than a soap opera plot, this paper neatly explains the step-by-step mechanics. They built a pipeline, mapped centromeres across loads of yeasts, ran clever simulations, did wet-lab checks and even showed that kinetochore proteins can evolve to tip the balance in favour of new centromere types. It’s a tidy package that saves you time and gives you a tested model for centromere change.

Author style

Punchy: the authors combine bioinformatics scale with targeted experiments to make a persuasive, mechanistic case that centromeres and kinetochores coevolve progressively. For geneticists and evolutionary biologists this is high-impact — it shifts centromere evolution from a purely abstract paradox to a demonstrable, testable pathway.