The Trump Administration’s Data Center Push Could Open the Door for New Forever Chemicals

Summary

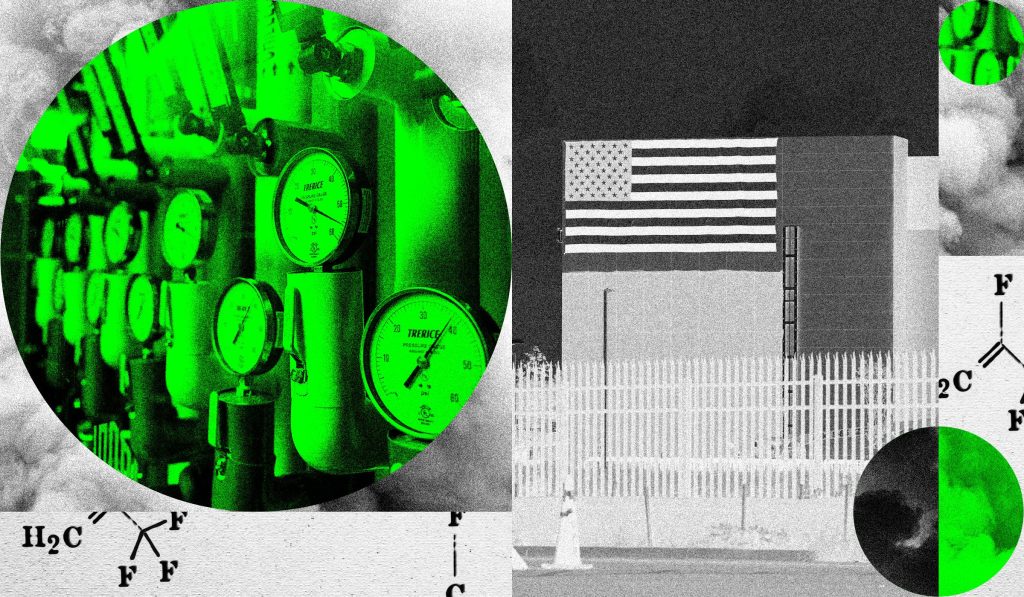

The EPA recently announced it will prioritise reviews of new chemicals tied to data centre or “covered component” projects, aiming to speed approvals to support rapid expansion of data infrastructure and AI-related developments. The policy is part of broader deregulatory moves and an AI Action Plan driven by the White House. Critics — including former EPA reviewers and environmental lawyers — warn the fast-track could be exploited to rubber-stamp new compounds with limited scrutiny, potentially including PFAS-like “forever chemicals” used in immersion cooling and semiconductor manufacturing.

The administration insists no steps of the new-chemical review will be skipped, but experts point to loopholes (such as reliance on letters from defence or commerce officials to qualify projects) and political pressure that could shorten careful evaluation. Industry players, including chemical firms and semiconductor lobbying groups, have pushed for faster reviews; companies like Chemours are developing two-phase immersion cooling fluids that may contain fluorinated compounds. Observers worry the change could broaden approvals beyond genuine data-centre needs, with wider public-health and environmental consequences.

Key Points

- The EPA will prioritise regulatory reviews for new chemicals claimed to be used in data centre or related “covered component” projects.

- Officials say the standard review process remains, but critics fear political pressure and loopholes could enable rapid approvals with less oversight.

- Two-phase immersion cooling — a way to lower data-centre cooling costs — often uses fluorinated fluids that resemble PFAS, a class of persistent “forever chemicals” linked to health risks.

- Chemicals used in semiconductor fabrication, another target of expedited review, are also common sources of new-chemical submissions and can involve PFAS-like compounds.

- Industry lobbying and meetings between EPA officials and semiconductor and chemical trade groups preceded the policy change, raising conflict-of-interest concerns among watchdogs.

- Companies such as Chemours and legacy chemical firms are developing or commercialising specialised cooling fluids; some advertise energy savings but face PFAS litigation histories.

- Although immersion cooling could reduce energy use significantly, regulators and companies in the EU and some US states are already tightening PFAS rules, which may limit adoption or create regulatory friction.

- Experts support clearing the EPA backlog and reforming the review process, but caution that prioritisation tied to data-centre projects risks long-term safety and environmental trade-offs.

Context and Relevance

Why this matters: data centres and chip fabs are central to the AI and cloud economy; accelerating their build-out without robust chemical review risks normalising the use of persistent, hard-to-remove compounds. The policy sits at the intersection of tech growth, industrial lobbying, environmental regulation, and public health — so its effects could ripple through supply chains, regional pollution burdens, and future regulation on PFAS and similar chemistries. For anyone tracking AI infrastructure, environmental policy, or chemical safety, this is a development that signals how industrial priorities can reshape regulatory practice.

Why should I read this?

Short answer: because this is one of those quietly big policy shifts that could let risky chemicals slide through under the guise of “speeding AI progress.” If you care about where your energy and chips come from, or about long-term pollution, this piece cuts through who’s pushing what and why — and saves you the time of digging through FOIA emails and press releases yourself.