Gene-specific selective sweeps are pervasive across human gut microbiomes

Summary

This Nature paper introduces a new LD-based statistic, iLDS (integrated LD score), to detect gene-specific selective sweeps driven by recombination and horizontal gene transfer in gut bacteria. Using simulations and metagenomic data from hundreds of human samples (quasi-phased haplotypes) and the UHGG catalogue, the authors show that recombination-mediated sweeps are widespread across commensal gut species. They detect hundreds of putative sweeps, find enrichment for carbohydrate metabolism and transport genes (notably starch/maltodextrin transporters mdxE/mdxF), and show many sweeps have spread across countries — especially among industrialised populations. The method is conservative (low false-positive rate) and code/data are publicly available.

Key Points

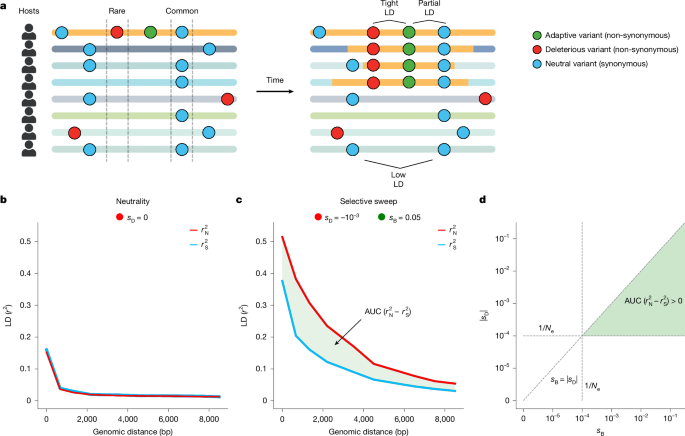

- iLDS combines excess LD among common non-synonymous variants over synonymous variants with locally elevated LD to pinpoint recombination-mediated selective sweeps.

- Simulations show the non-synonymous LD excess (versus synonymous) is a signature of sweeps when purifying selection keeps most non-synonymous variants rare but allows hitchhiking.

- Analysis of 3,316 quasi-phased haplotypes across 32 gut species found significant signatures of selection in 26 species and 155 unique sweeps overall (447 genes).

- Application to UHGG (24 populations, 16 species) uncovered 309 unique sweeps, many population-specific but with dozens shared across continents.

- Genes involved in carbohydrate transport and metabolism (e.g. susC/susD and mdxEF maltodextrin transporters) are recurrent sweep targets — suggesting diet-linked adaptation, especially in industrialised populations.

- The mdxEF sweep in Ruminococcus bromii is ubiquitous in industrialised populations but absent in some non-industrialised groups, pointing to adaptation to modern/processed diets.

- iLDS is conservative (false positive rate <1% under neutrality in tests) and recovers known sweeps in organisms such as C. difficile and H. pylori, and known sweep loci in Drosophila.

- Code and data are available (GitHub: github.com/garudlab/iLDS; data deposited on Dryad/Zenodo), enabling reproducibility and follow-up functional work.

Content summary

The authors first motivate why comparing LD among non-synonymous versus synonymous variants helps control for demographic and non-selective forces that also elevate LD. They validate this approach with forward-time simulations, demonstrating the distinct signature produced by recombination-mediated gene-specific sweeps when purifying and positive selection act concurrently.

They then extract quasi-phased haplotypes from shotgun metagenomes (693 individuals) and calculate r_N^2 and r_S^2 decay curves. Across 32 prevalent commensal species, most show a significant excess of non-synonymous LD among common variants, consistent with widespread purifying and positive selection.

To localise sweeps, they develop iLDS, which combines AUC(r_N^2 – r_S^2) with local LD elevation relative to genome-wide expectation, standardises both components and computes iLDS per sliding window. iLDS recovers known sweeps (for example tcdB and S-layer loci in C. difficile) and identifies many new candidates.

Across datasets, the team reports hundreds of candidate gene-specific sweeps, with functional enrichment for carbohydrate metabolism and repeated hits on genes like mdxEF. Using UHGG assemblies from industrialised and non-industrialised populations, they show many sweeps are population-specific, while a meaningful fraction is shared — and industrialised populations share sweeps with one another more than with non-industrialised populations.

The authors conclude that homologous recombination and short fragment transfer is a principal route for spreading adaptive DNA in gut commensals, often targeting nutrient acquisition genes, and that diet/lifestyle likely shapes these evolutionary trajectories. They stress iLDS’s conservatism and the need for follow-up molecular work to confirm functional effects.

Context and relevance

This work sits at the intersection of microbial population genetics, microbiome ecology and human environmental change. It demonstrates that adaptive evolution in the gut is not solely about species turnover but often about gene-scale changes moving between strains by recombination and HGT. That carbohydrate-processing genes repeatedly come up as targets ties microbial evolution directly to diet and the rise of ultra-processed foods; the finding that industrialised populations share particular sweeps strengthens the link between lifestyle and microbial evolution.

For researchers this provides a new, tested method (iLDS) to scan recombining microbes for recent adaptive events. For clinicians, nutrition scientists and probiotic developers it highlights candidate genes and pathways whose evolutionary dynamics could impact host metabolism, inflammation or therapeutic responses.

Why should I read this?

Short version: if you care about how your gut bugs change and why — especially in response to diet and modern lifestyles — this paper gives you a ready-made detector (iLDS), real-world evidence that gene-scale adaptations are everywhere, and a shortlist of genes to watch (think starch and maltodextrin transporters). It’s dense but packed with results you can actually use in follow-up lab or cohort work.

Author note (style)

Punchy takeaway: recombination shuffles winning gene fragments between strains, and the gut microbiome is evolving in human populations in predictable ways. The methods are conservative, the signals broad, and the diet link is obvious enough to be worrying — and interesting.