These women helped to shape quantum mechanics — it’s time to recognise them

Summary

Nature reviews the anthology Women in the History of Quantum Physics (edited by Patrick Charbonneau et al.), which collects essays that recover and reassess the contributions of women to quantum physics. The book challenges the long-standing idea of quantum theory as a young men’s club (Knabenphysik) by presenting a situated–relational history: researchers and their work are understood in the context of social position, institutions and interpersonal networks. The review highlights examples such as Williamina Fleming — whose spectral discoveries were credited to her employer — and experimentalist Chien‑Shiung Wu, whose early entanglement experiments prefigured later celebrated work. Overall, the anthology calls for a broader, more complex narrative of quantum physics that accounts for marginalised actors and hidden labour.

Key Points

- The anthology foregrounds 16 women whose work shaped quantum theory and related fields but has often been overlooked or misattributed.

- Williamina Fleming’s spectral discoveries aided atomic theory yet were named after her employer — an example of how women’s labour was obscured.

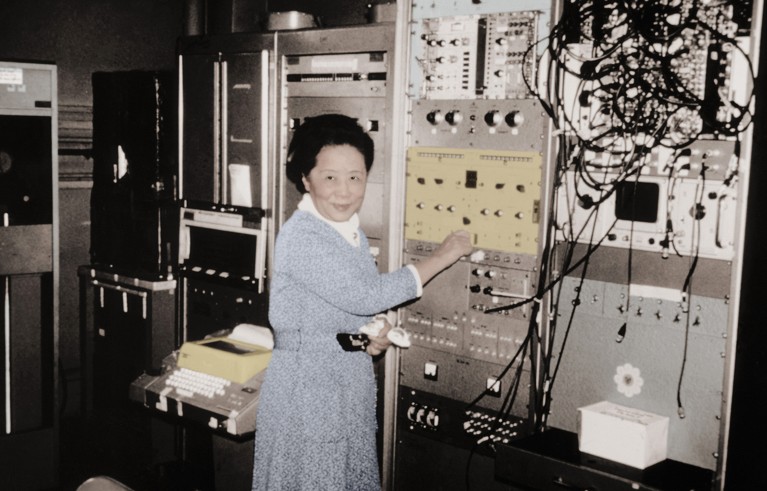

- Chien‑Shiung Wu produced early experimental evidence for photon entanglement (1950) and later refined tests of quantum foundations, but her role is less remembered than some male counterparts.

- The editors advocate a situated–relational approach: understanding physics requires attention to social context, institutions and interactions, not only celebrated theories and names.

- The book is both corrective and methodological — it challenges historians and scientists to expand the narratives we accept about who made key advances.

Context and relevance

This review matters because it reframes the history of quantum physics at a time when discipline histories and recognition practices are under scrutiny. By documenting overlooked contributions, the anthology affects how we think about credit, citation, and the composition of scientific canons — with knock‑on effects for hiring, awards and teaching. It also links historical recovery to contemporary debates about diversity, labour division and who counts in scientific stories.

Why should I read this?

Because it’s a neat, sharp corrective — the kind of read that makes you say “why didn’t I know that?” It saves you time by pulling together persuasive examples showing how women’s work was essential but often invisible, and it gives you tools to question the standard tales of quantum physics.

Author style

Punchy and pointed: the reviewer emphasises that this anthology doesn’t just add names to a list but forces a rethink of methods and narratives. If you care about who gets credit in science — and why — the review makes the case that the book is essential reading.