A mechanical ratchet drives unilateral cytokinesis

Article metadata

Article Date: 07 January 2026

Article URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09915-x

Article Image: Figure 1

Summary

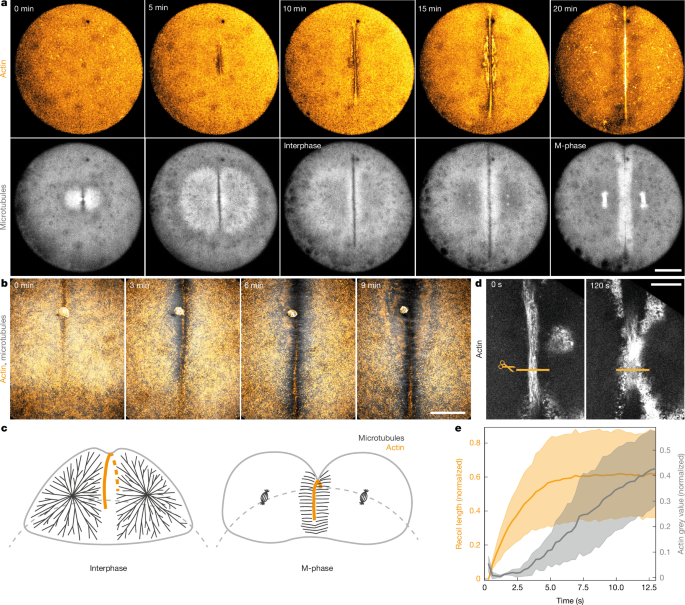

This study uses zebrafish blastomeres to explain how an open-ended actomyosin band — not a closed contractile ring — can drive cell division in very large embryonic cells. Through laser ablation, photoactivatable microtubule inhibitors, magnetic and optical tweezers, ferrofluid droplets and computational modelling, the authors show that interphase microtubule asters stiffen the bulk cytoplasm and mechanically anchor the contractile band along its length. When the cell enters M-phase, microtubule asters disassemble, the cytoplasm fluidises, and the previously anchored band is able to ingress. Alternating cycles of stiff (interphase) and fluid (M-phase) cytoplasm act like a temporal mechanical ratchet: growth and stabilisation of the band in interphase, then faster ingression in M-phase, repeated until cleavage completes.

Key Points

- Unilateral cytokinesis in large early embryonic cells occurs with an open-ended contractile actin band rather than a fully closed ring.

- Laser ablation shows the forming actin band is contractile but locally anchored, preventing collapse despite loose ends.

- Microtubules (interphase asters) mechanically anchor the band; rapid microtubule depolymerisation causes band retraction and cytokinesis failure.

- Magnetic and optical tweezers plus ferrofluid droplets reveal the cytoplasm is ~threefold stiffer in interphase (with asters) than in M-phase (without asters).

- Fluidisation in M-phase enables much faster furrow ingression; band contractility itself does not change significantly between phases.

- A viscoelastic (Jeffrey’s) model reproduces observed behaviour: alternating stiff/solid and fluid states produce a ratchet-like progression of furrow ingression over successive cycles.

- The mechanism explains why rapidly dividing, yolky embryos (zebrafish, amphibians, birds, reptiles, some mammals) use unilateral cleavage instead of a complete ring.

Content summary

The authors imaged zebrafish first divisions and used femtosecond laser ablation to test whether the forming actin band is contractile and how it avoids collapse. Recoil after cuts confirmed contractility, but repeated cuts showed portions of the band can still ingress if anchored locally. Subsequent experiments showed the actin cortex and membrane are not sufficient anchors. Photoactivatable microtubule inhibition and injected obstacles demonstrated that interphase microtubule asters provide mechanical anchoring along the band.

Rheological measurements (magnetic and optical tweezers) and ferrofluid deformation experiments quantified a marked stiffening of the cytoplasm during interphase driven by bulk microtubule asters. When asters disassemble in M-phase the cytoplasm fluidises, permitting rapid furrow ingression. Directly depolymerising asters during interphase increases ingression speed before the band eventually collapses, showing that changes in cytoplasmic material properties are sufficient to change ingression dynamics.

A computational model of the cell as a viscoelastic sphere with a growing contractile band recapitulates the experimental ingression pattern by switching material parameters between stiff (interphase) and fluid (M-phase). From this, the authors propose a temporal mechanical ratchet: interphase stabilises and extends the band; M-phase fluidises the cytoplasm and allows ingression; cycles repeat until cleavage is achieved.

Context and relevance

This work reframes cytokinesis in large, yolky embryonic cells: instead of a purse-string ring, division relies on spatially distributed anchoring by microtubule asters plus cell-cycle-dependent rheology changes. It connects cytoskeletal organisation, intracellular mechanics and cell-cycle timing to explain a conserved developmental strategy (unilateral cleavage) across diverse species. The findings matter if you study early development, cytoskeleton mechanics, or biophysical regulation of morphogenesis — and they provide a clear mechanochemical model that can be tested in other large-cell systems.

Why should I read this?

Quick answer: because the paper explains a long-standing oddity — how a ‘loose’ actin band can actually divide huge embryonic cells — with clean experiments and a tidy physical model. If you care about how cells harness mechanical states rather than just biochemical signals to do work, this is a compact, clever read that saves you the slog of digging through fragmented literature on unilateral furrows and cytoplasm rheology.

Author note (punchy)

Punchline: microtubules stiffen, the band anchors, mitosis fluidises and the furrow bites. Repeat — that’s the ratchet. Big implication: cell-cycle timing and bulk mechanics can substitute for a closed ring to get the job done fast in enormous embryonic cells.