A young progenitor for the most common planetary systems in the Galaxy

Summary

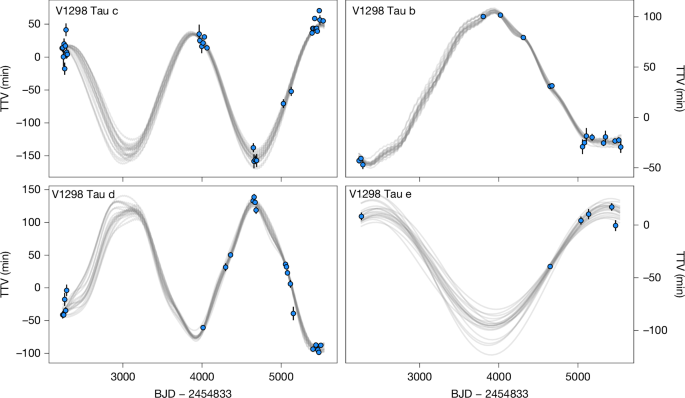

The paper reports a multi-year transit-timing-variation (TTV) campaign that characterised the young (≈10–30 Myr) star V1298 Tau and its four transiting, unusually large planets. By recovering the outer planet’s orbital period and modelling 9 years of transit data with analytic intuition followed by full N-body fits, the authors measure low, sub-Neptune masses and nearly circular orbits for all four planets.

Key measured masses: M_c = 4.7 ± 0.6 M_⊕, M_d = 6.0 ± 0.7 M_⊕, M_b = 13.1 ± 5.3 M_⊕, M_e = 15.3 ± 4.2 M_⊕. The planets are very low density for their sizes today, implying they are inflated, hydrogen-rich worlds that will contract over time to join the abundant super-Earth/sub-Neptune population.

Key Points

- Multi-year TTV campaign (2015–2024) recovered V1298 Tau e and produced robust masses and orbital parameters despite strong stellar activity.

- All four planets have low masses and densities and nearly circular orbits — a dynamically tranquil architecture that is long-term stable and non-resonant.

- The inner planets (c and d) have masses and radii that require a low-entropy formation state (“boil-off”) soon after disk dispersal.

- TTVs provide more reliable mass constraints here than radial velocities because stellar activity overwhelms expected RV signals.

- Evolutionary models predict contraction to ≈1.5–4.0 R_⊕ over Gyr timescales, producing planets that populate the Kepler-era radius valley and the common sub-Neptune population.

Context and relevance

V1298 Tau gives astronomers a rare snapshot of a compact, multi-planet system at an age immediately after formation. The system sits in an under-sampled region of the period–radius plane: large radii at young age but low masses. That combination is a direct test of planet-formation and early-evolution theories (core accretion, boil-off, photoevaporation) and helps explain how the now-common super-Earths and sub-Neptunes acquire their final sizes.

The study also demonstrates the power of long-baseline TTVs and modern N-body modelling — especially for young, active stars where Doppler methods struggle. It ties to ongoing trends: JWST atmospheric follow-ups, improved TTV/N-body tools, and population-scale efforts to map the radius valley’s origin.

Why should I read this

Short version: this is basically a baby‑photo of the kinds of compact systems Kepler found in bulk. If you care about how planets shed or hold on to atmospheres, why many systems end up as super‑Earths or sub‑Neptunes, or how to measure planet masses when the star is a hyperactive teenager, this paper is a time‑saving must — the authors did the heavy lifting and show the physics in action.

Author style

Punchy: the team combines careful long-term observations with modern analytic and N-body TTV modelling to produce robust, validated masses; the result is a clear, high‑impact data point for early planetary evolution that will be widely cited in formation and atmospheric-evolution work.

Source

Article Date: 07 January 2026

Article URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09840-z

Article Image: Figure 1 (TTVs)