Mysterious cosmic ‘dots’ are baffling astronomers. What are they?

Summary

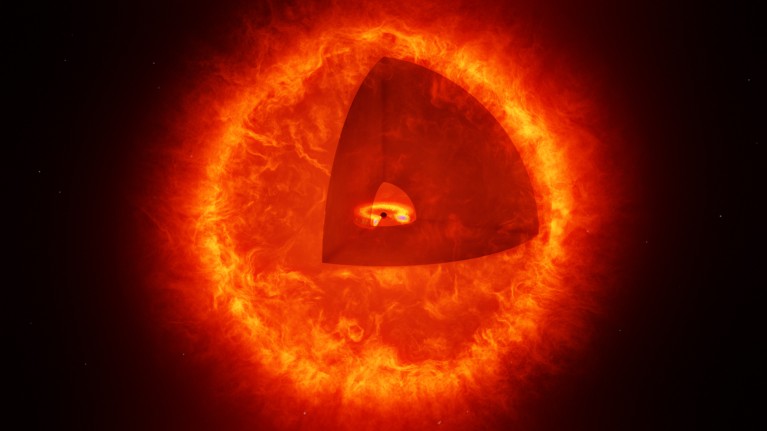

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has revealed hundreds of tiny red sources in very distant, early-universe images. Initially puzzling because they were too compact to be regular galaxies and didn’t match expected black-hole signatures, these “little red dots” (LRDs), sometimes called rubies, are now widely interpreted as a new class of object: an active black hole enshrouded in hot, dense gas — effectively a “black-hole star.” Key evidence includes a striking object nicknamed the Cliff, whose abrupt spectral break rules out many other models. Researchers are exploring how these objects form, whether they evolve into galaxy centres, and how common they might be across cosmic time.

Key Points

- JWST discovered numerous compact, red sources in early-universe images that did not fit known categories.

- Leading explanation: LRDs are hybrid objects — an active black hole wrapped in a dense, warm gas envelope that glows (a “black-hole star”).

- The object called the Cliff shows a sharp spectral break that strongly supports the black-hole-star model and rules out ordinary galaxies.

- Some LRDs are found inside large dark-matter haloes with nearby galaxies, suggesting they could become galactic centres or be linked to early quasar activity.

- About 200 preprints have appeared since 2022; many questions remain about formation, evolution and how widespread LRDs are beyond the very early Universe.

Content summary

When JWST peered back to the Universe’s infancy it revealed tiny red specks that at first looked inexplicable. Their compactness and long-wavelength emission conflicted with expectations for early galaxies and standard black holes.

Recent analyses have coalesced around a novel idea: these dots are active black holes submerged in a cocoon of hot, dense gas that radiates in the infrared. This configuration can reproduce the unusual spectra observed, including the dramatic spectral cliff seen in one particularly telling source.

Further studies show some LRDs sit in massive dark-matter haloes and near multiple galaxies, hinting that they might grow into the luminous centres of galaxies or be early stages of quasar formation. The rapid pace of follow-up work — hundreds of manuscripts in a few years — means the field is moving quickly but is still unsettled on formation channels and later evolution.

Context and relevance

This story matters because it may reveal a previously unknown astrophysical phenomenon from the epoch when the first structures formed. If LRDs are indeed black holes wrapped in stellar-like gas envelopes, they force a rethink of how massive black holes and galaxy centres form and light up in the early Universe. The discovery leverages JWST’s unprecedented sensitivity in the infrared and feeds into broader debates about early black-hole growth, reionisation and structure formation. For astronomers and anyone following JWST-driven surprises, LRDs are a major thread to watch.

Why should I read this?

Short version: it’s weird, new and could change how we think the first cosmic objects grew. The article cuts through the chatter and points out why the “black-hole star” idea fits the strange data. If you like cosmic mysteries, early-Universe drama or JWST tea, this is a neat clutch of results that saves you wading through dozens of papers.