People with some cancers live longer after a COVID vaccine

Article Date: 22 October 2025

Article URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-03432-7

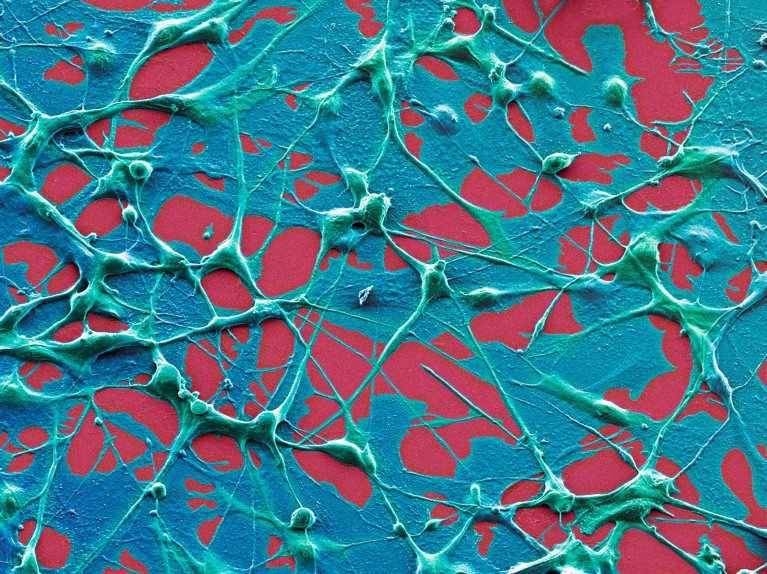

Image: Melanoma cells image

Summary

Analysis of medical records and supporting mouse experiments suggest that mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines can boost the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors for some cancers. In a review of more than 1,000 people with lung cancer or melanoma, researchers observed substantially longer survival among patients who had an mRNA vaccine close to the start of their cancer treatment. Mouse studies indicate the effect is not due to preventing COVID-19 but to a broad activation of the immune system that helps the tumour become more susceptible to immunotherapy.

Key human findings included a near doubling of median survival in a subgroup of lung-cancer patients (from about 21 to 37 months) and greatly extended survival in vaccinated people with metastatic melanoma (median not yet reached). The boost was largest for tumours that would otherwise be unlikely to respond to checkpoint inhibitors. Timing matters: benefits were strongest when vaccination occurred within roughly 100 days of starting treatment, with preliminary data hinting at an even narrower optimal window.

Key Points

- mRNA COVID-19 vaccines appear to act as a systemic immune stimulant that can sensitize tumours to checkpoint-inhibitor immunotherapy.

- Analysis of >1,000 patients with lung cancer or melanoma found markedly longer survival in those vaccinated with an mRNA jab near the start of treatment.

- In one lung-cancer subgroup median survival rose from ~21 to ~37 months after vaccination.

- Vaccinated patients with metastatic melanoma had such extended survival that a median could not be calculated by study end.

- The biggest benefits were seen in tumours predicted to be poor responders to checkpoint inhibitors.

- Mouse experiments support a mechanism of immune activation and increased tumour infiltration, rather than protection from SARS-CoV-2.

- Timing is important: vaccination within ~100 days (and possibly within a 30-day window) of starting therapy gave the strongest signal.

- Findings are promising but observational; clinical trials are needed to confirm causation and define optimal timing and patient groups.

Why should I read this?

Short version: this could be huge. If you care about cancer treatments (or know someone who does), the idea that a routine mRNA COVID jab might make immunotherapy work better is worth a glance. It’s not a miracle cure yet, but the data are surprising and potentially practice-changing — so you’ll want to know the basics without wading through the paper.

Context and Relevance

This story ties into two major trends: the rapid maturation of mRNA technology and the ongoing drive to improve cancer immunotherapy. Checkpoint inhibitors transformed oncology but fail in many patients because the immune system sometimes ignores tumours. The new analysis implies that a broad immune stimulus from an mRNA vaccine can ‘wake up’ the immune response and improve outcomes when combined with checkpoint blockade.

Implications: if confirmed in trials, this could offer a relatively accessible adjunct to existing immunotherapies, speeding adoption compared with bespoke personalised cancer vaccines. It also highlights the need for prospective studies to nail down which patients benefit, the best timing, and whether different mRNA vaccines behave similarly. Policy and funding decisions (for example recent cuts to some mRNA research budgets) will shape how quickly these findings can be translated into clinical practice.