What changing energy flows reveal about Africa’s ecosystems

Article Date: 29 October 2025

Article URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-03215-0

Author: Wendy Foden

Summary

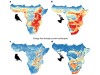

Animals are not just present in ecosystems — they move and transform energy. This News & Views piece highlights a new approach (Loft et al., Nature) that converts species-composition data into a common currency: energy flow. By measuring how much energy different animals process, the method reveals widespread declines in the ecological roles animals play across sub-Saharan Africa as large-bodied populations fall.

The piece explains why tracking energy flow is powerful: it ties species losses to concrete functions such as carbon cycling, nutrient redistribution, pollination and decomposition. Losses of megafauna cause disproportionate drops in these flows, meaning ecosystems can lose function even when species counts drop only a little.

Key Points

- Loft et al. present an energy-flow framework that translates animal community composition into units of energy processed by consumers.

- Across Africa, declines in large animals lead to measurable reductions in ecosystem functions like nutrient cycling and carbon movement.

- Energy-flow metrics capture functional change that species counts alone can miss — especially when large-bodied species decline.

- The approach provides a standardised way to compare functional loss across regions and taxa and to link biodiversity change to ecosystem services.

- Using energy as a common currency could guide monitoring, conservation prioritisation and policy by focusing on functional outcomes, not only species lists.

Context and relevance

This interpretation matters because conservation is increasingly judged by ecosystem function and service provision, not only by species presence. As climate change, land-use change and hunting continue to alter animal communities, tools that quantify functional loss help bridge ecology and policy. The energy-flow perspective also complements existing metrics (such as biomass or abundance) and can expose hidden declines in ecological processes driven by losses of big animals.

Why should I read this?

Quick and blunt: if you care about whether ecosystems still do the jobs we rely on — storing carbon, recycling nutrients, pollinating crops — this is worth a read. The piece shows a neat trick: turn messy species data into a single, actionable number (energy flow) that tells you whether systems are still working. Saves you time by pointing to a metric that policymakers and ecologists can actually use.