ZAK activation at the collided ribosome

Summary

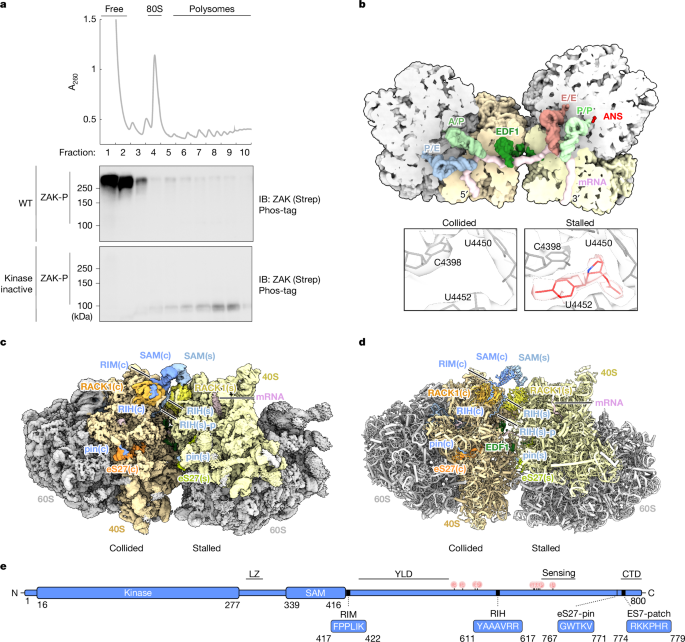

This Nature paper uses cryo-electron microscopy, CLIP-seq and biochemical/mutational analysis to show how the MAP3K ZAK (ZAKα) recognises and is activated by collided ribosomes. The authors present a composite structure of ZAK bound to a disome (a stalled ribosome plus a colliding ribosome) and map multiple ZAK interaction motifs: a C-terminal “pin” that grips eS27 and contacts rRNA ES7, a RACK1-interacting helix (RIH) that anchors ZAK to RACK1, and a collision-specific RACK1-interacting motif (RIM, an FPxL-like sequence) that only engages on collision. Dimerisation of ZAK SAM domains across the two RACK1s forms a bridge that licences kinase activation. The study also identifies SERBP1 as a competitor at the FPxL site that limits spurious activation, and shows that disease or engineered SAM mutants can bypass ribosome-dependent regulation to become constitutively active.

Key Points

- ZAK surveys ribosomes via C-terminal contacts: an eS27 “pin” and interactions with 18S rRNA ES7 (sampling mode).

- The RIH motif binds RACK1 and helps recruit ZAK to 40S independent of collisions.

- The RIM (FPxL-like) motif binds RACK1 only on collided disomes and is strictly required for ZAK activation.

- SAM domains from two ZAK molecules dimerise across the collision interface (RACK1–RACK1 bridge) and this dimerisation is the key step that licences autophosphorylation and downstream SAPK (p38/JNK) signalling.

- SERBP1 occupies the same FPxL-binding pocket on RACK1 and acts as a negative regulator, reducing accidental activation under basal conditions.

- Mutations that disrupt pin or RIH reduce ribosome binding and activation; SAM-interface mutants can be hyperactive or inactive, showing the SAM dimer controls catalytic output and can bypass the ribosomal trigger when mutated.

- Combining structural, CLIP-seq and cell-based assays provides a coherent model: ZAK samples ribosomes but only on stable disomes (collisions) does the RIM–RACK1 interaction and SAM dimer enable activation.

Content summary

The study begins by enriching ZAK-bound ribosomes through overexpression of inactive ZAK variants, then isolates ZAK–ribosome complexes for cryo-EM. High-resolution maps reveal multiple ZAK contact points: (1) a C-terminal ribosome-binding region (RBR) whose short “pin” motif (W768 etc.) inserts into eS27 and positions the positively charged CTD close to ES7; (2) a RACK1-interacting helix (RIH, residues ~611–617) that anchors ZAK to RACK1; and (3) a collision-specific RACK1-interacting motif (RIM; FPPLIK) that engages only when two RACK1s are juxtaposed in a disome.

CLIP-seq corroborates rRNA contacts (ES7 enrichment at baseline; ES6b/c enrichment on ANS-induced collisions). Functional mutagenesis shows pin and ES7-patch mutations reduce ribosome binding and block activation, whereas RIH mutations abolish binding and activation. RIM mutants still bind constitutively but fail to activate and persist on polysomes after collision induction, indicating RIM is essential for the collision-sensing activation step rather than basal recruitment.

The SAM domains form an asymmetric head-to-tail dimer that bridges the two RACK1s only when the disome interface is present. Mutations at the SAM–SAM interface produce a spectrum of activity phenotypes, including hyperactive disease-associated and engineered mutants (e.g. F368C, K387D) that become constitutively active and are degraded unless stabilised by inhibitors. SERBP1 is identified bound at the RIM site on RACK1 and knockdown of SERBP1 increases JNK phosphorylation, supporting a model of competition for the FPxL pocket as a basal brake on activation.

Overall, the work proposes a clear mechanistic model: ZAK samples ribosomes via pin/RIH contacts; on stable collisions the RIM engages both RACK1s, enabling SAM dimerisation, kinase autophosphorylation and release to engage downstream stress signalling. Pathogenic SAM mutants can bypass this regulation and activate independently of ribosomal cues.

Author’s take

Punchy: this is a clean structural and functional dissection showing how a kinase reads out a mechanical event on the translation machinery. If you care about how cells sense translational trouble and decide between repair, arrest or death, these molecular details matter.

Why should I read this?

Short version — read this if you want to know exactly how ribosome collisions get turned into a kinase signal. The paper ties together structure, RNA crosslinking and clever mutations to show that ZAK doesn’t just bind ribosomes randomly: it “samples” monosomes but only flips the switch when the collision-specific RIM and SAM dimer come together. Also, the SERBP1 competition idea gives a neat explanation for why cells don’t trigger the ribotoxic stress response all the time. Good for anyone working on translation quality control, stress signalling or kinase regulation.