Inhibitors supercharge kinase turnover through native proteolytic circuits

Summary

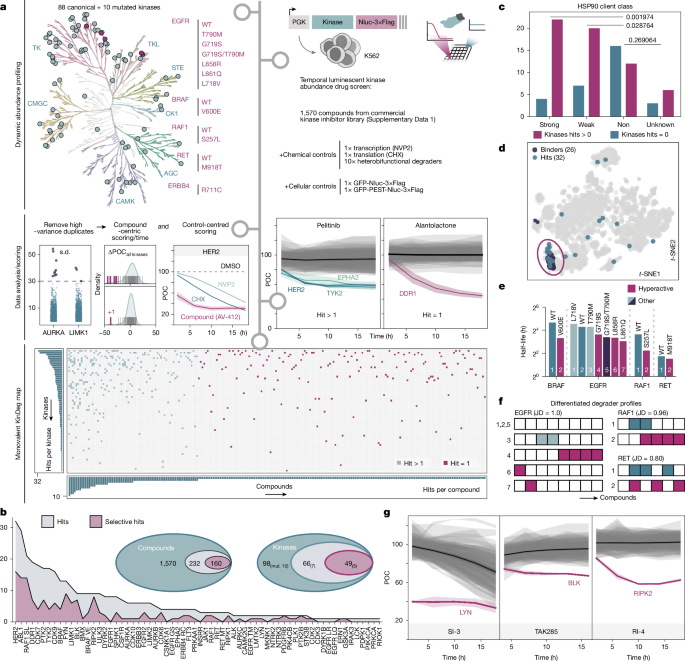

This Nature study reports a systematic, large-scale screen showing that many ATP-competitive (monovalent) kinase inhibitors do more than block enzymatic activity — they can accelerate degradation of their kinase targets by engaging native cellular proteolytic pathways. The authors profiled 98 kinase constructs (88 wild-type and 10 mutants) expressed as nanoluciferase fusions in K562 cells and treated them with 1,570 kinase inhibitors. They identify 232 compounds that downregulate at least one kinase and 66 kinases affected overall. While HSP90 chaperone deprivation explains many events, multiple distinct mechanisms beyond chaperone loss were discovered. Detailed follow-up of three examples (LYN, BLK and RIPK2) established a unifying concept the authors call “supercharging”: inhibitors induce or stabilise kinase states that are preferentially recognised by endogenous degradation circuits, producing rapid target turnover.

Key Points

- A high-throughput luminescent reporter screen (98 kinases × 1,570 inhibitors) found 232 destabilising compounds and 66 kinases with reduced abundance.

- HSP90 client kinases are enriched among degradable targets, confirming chaperone deprivation as a common route, but many degradation events occur by different mechanisms.

- Inhibitor-induced degradation does not correlate with PROTAC degradability — monovalent degradation is mechanistically distinct from proximity-based degradation.

- Mutant kinases show qualitatively different susceptibilities versus wild-type kinases; enhanced degradability is not explained solely by reduced half-life.

- LYN is rapidly degraded by SI-3 through a network effect: SI-3 preferentially inhibits CSK, which leads to LYN activation and recruitment of CBL/CBLB E3 ligases that drive ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal and lysosomal turnover.

- BLK is degraded by TAK285 via an unexpected γ-secretase-dependent mechanism: TAK285 treatment causes loss of BLK myristoylation and membrane release (γ-secretase cleavage of the N-terminal anchor), exposing an unstable cytosolic N-terminus and rapid proteolysis.

- RIPK2 is destabilised by RI-4 through induced higher-order assemblies (RIPosome-like multimers). TMUB1 facilitates their formation and macroautophagy/lysosomal clearance (involving Lys63 ubiquitination and IAP-family E3s).

- These examples illustrate three general ways inhibitors can “supercharge” native turnover circuits: by altering activity (LYN), localisation (BLK) or assembly state (RIPK2).

- Practical implication: inhibitor off-targets or polypharmacology can produce potent, selective degradation via network effects — important for both therapeutic benefit and adverse events.

Content summary

The authors implemented a nanoluciferase fusion reporter library in K562 cells to read target abundance over time and applied rigorous controls to filter out transcription/translation artefacts. They measured temporal trajectories at multiple timepoints and applied a multi-scheme scoring pipeline to call destabilising compounds. The screen produced a binary KinDeg map and identified frequent hits such as HER2, ABL1 and RAF1(S257L).

Although HSP90-client status strongly associates with susceptibility — consistent with the chaperone-deprivation model — in-depth mechanistic work uncovered additional, diverse routes to degradation. SI-3 depletes LYN within minutes by engaging a physiological activity–stability switch: SI-3 targets CSK (a negative regulator), which disinhibits LYN, prompting CBL/CBLB recruitment and ubiquitin-mediated clearance via both proteasome and lysosome. TAK285 downregulates BLK not by orthosteric BLK inhibition but by provoking γ-secretase-dependent cleavage of BLK’s myristoyl anchor, causing membrane-to-cytosol relocalisation and exposure of an unstable N-terminus; residue-level scanning defined a minimal N-terminal motif required for this effect. RI-4 binds RIPK2 and promotes CARD-dependent multimerisation resembling physiological RIPosome formation; TMUB1 helps assemble these structures which are then removed by macroautophagy and lysosomal degradation, involving IAP-family E3 ligases.

Overall, the authors define “supercharging” as the capacity of a ligand to accelerate existing cellular degradation pathways by stabilising a recognisable degradation-prone state of the protein, offering a unifying framework for many monovalent degrader phenomena beyond proximity-induced degradation.

Context and relevance

This work has immediate relevance for drug discovery, chemical biology and clinical pharmacology. Kinase inhibitors are among the most clinically used targeted small molecules, and understanding how inhibitors influence protein abundance helps explain efficacy differences, mutant selectivity and adverse effects. The discovery that inhibitors can trigger native proteolytic routes (including an unexpected γ-secretase-dependent release of a myristoylated anchor) widens the mechanistic repertoire available to exploit for targeted protein reduction. The KinDeg dataset and mechanistic vignettes provide a resource to anticipate drug-induced degradation, inform lead optimisation and explore therapeutic strategies that harness endogenous turnover without engineering PROTACs or bivalent glues.

Author style

Punchy: this is not just another screening paper — it reframes how we think about small-molecule action on kinases. The detailed mechanistic triad (LYN, BLK, RIPK2) convincingly shows that inhibitors can deliberately or inadvertently co-opt physiological degradation circuits. For anyone designing kinase-targeting drugs or studying kinase biology, the full methods and dataset are worth digging into; they could change both how you interpret drug action and how you design next-generation degraders.

Why should I read this?

Because it’s one of those papers that saves you time and makes you rethink assumptions. If you work with kinase inhibitors, drug discovery or targeted degradation, this study explains why some inhibitors mysteriously lower protein levels and gives concrete mechanisms and examples. It’s got a big dataset, clever follow-ups and surprising biology (yes, γ-secretase cutting off a myristoyl anchor). Short version: it explains weird drug effects and points to new design tricks — skim for the dataset, read the LYN/BLK/RIPK2 sections properly.