Homo sapiens-specific evolution unveiled by ancient southern African genomes

Article metadata

Article Date: 03 December 2025

Article URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09811-4

Article Image: Figure 1

Summary

This Nature study reports whole-genome sequences from 28 ancient individuals from south of the Limpopo River (South Africa), dated across the Holocene (10.2 ka to a few hundred years ago). Seven genomes exceed 7.2× coverage and are analysed in depth. The authors identify a distinct “ancient southern African” ancestry component present in individuals from ~10.2–1.4 ka with evidence of population continuity for at least 7 kyr. Genetic divergence between this southern lineage and other human groups is estimated at roughly 240–310 ka, placing it among the deepest population splits within Homo sapiens. Gene flow into southern Africa from eastern and western Africa is only clearly detectable after ~1.3 ka, matching archaeological evidence for later movements. The ancient southern genomes carry many Homo sapiens-specific amino-acid altering variants — many private to this region — with enrichment in immune-related and kidney-function genes. The data suggest southern Africa acted as a long-term refugium with long periods of isolation, and show that some candidate ‘fixed’ human-specific variants (for example, TKTL1) are variable in these and modern Indigenous southern African groups.

Key Points

- 28 ancient genomes from southern Africa (Holocene) were sequenced; 7 high-coverage genomes are studied in detail.

- An “ancient southern African” ancestry component is present in individuals spanning ~10.2–1.4 ka, showing population continuity over millennia.

- Estimated divergence between ancient southern Africans and other groups is ≈240–310 thousand years ago — one of the deepest splits in Homo sapiens.

- Significant gene flow into the region from eastern and western Africa appears mainly after ~1.3 ka, consistent with archaeological and linguistic shifts.

- Modern Khoe-San groups retain substantial ancient southern ancestry (~79% on average in least-admixed genomes), but recent admixture has altered present-day profiles.

- The ancient southern genomes contain many Homo sapiens-specific amino acid–altering variants; ~50% of such variants in this dataset are unique to ancient southern Africans.

- Functional enrichment among fixed Homo sapiens-specific variants implicates immune-system and kidney-function genes, suggesting adaptation related to immunity and water conservation.

- Some previously reported “fixed” human-specific variants (e.g. in TKTL1 linked to neurogenesis) are variable in these ancient genomes and modern Indigenous southern African populations, cautioning against over-generalising from limited samples.

Content summary

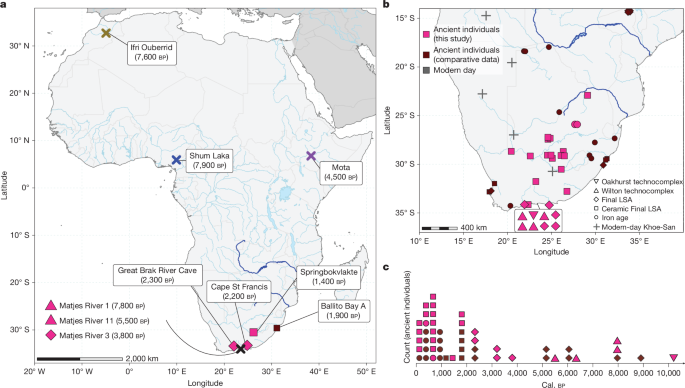

The authors sampled widely across southern and central parts of South Africa and combined their ancient genomes with comparative ancient and modern datasets. Population structure analyses (PCoA, ADMIXTURE, f-statistics) place ancient southern Africans on an extreme end of human genetic variation, distinct from eastern, western and central African groups. Using the oldest high-coverage individual as an anchor, they demonstrate continuity across several thousand years, and show that admixture signals from other African regions only become prominent after ~1.3 ka.

The paper performs diploid genotype calling on high-coverage genomes and examines the full spectrum of variation, focusing on derived amino-acid altering sites that are fixed among modern 1KGP samples but variable in these ancient genomes. They find hundreds of Homo sapiens-specific amino-acid changes fixed in ancient southern Africans and hundreds of thousands of variable sapiens-specific sites overall, many private to these genomes. Gene ontology analyses highlight kidney function and immune processes among enriched categories. Population-size reconstructions indicate a large long-term effective population size in southern Africa, with modest declines around the Last Glacial Maximum and hints of fragmentation during the Holocene.

Methods include targeted ancient-DNA extraction, UDG treatment, capture for low-endogenous samples, mapping to hs37d5, contamination checks, haplogroup assignments and a range of population-genetic tools (ADMIXTURE, MSMC, PCoA, f-statistics, two-by-two site-frequency spectra for divergence dating). Data and variant calls are deposited at Zenodo and the European Nucleotide Archive (PRJEB98562).

Context and relevance

This study matters because it substantially increases the number of complete ancient genomes from southern Africa and directly addresses debates about where modern human diversity originated and how population structure in Africa shaped Homo sapiens evolution. The results support a model of deep population stratification and long-term refugia in southern Africa, rather than a single, pan-African panmixia. The discovery of many region-specific Homo sapiens variants — and the fact that some presumed “fixed” changes are not universal — is important for evolutionary biology, palaeoanthropology and medical genetics. It emphasises that broader sampling of Indigenous and ancient genomes is essential before drawing broad inferences about human-specific adaptations in cognition, physiology and disease susceptibility.

Author style

Punchy: This is a high-impact, data-rich paper. If you follow human origins, ancient DNA or trait evolution, the full methods, variant lists and functional analyses are worth reading in detail — the authors provide complete genomes and variant calls, not just summaries.

Why should I read this?

Short answer — because it flips a few sloppy assumptions. These genomes show southern Africa was a long-lived genetic refuge with huge, partly private variation. That means (a) some “human-specific” mutations aren’t as universal as we thought, and (b) southern Africa holds evolutionary signals you won’t see in more sampled populations. If you’re interested in where modern human traits came from, or want variant sets relevant to immunity and kidney function, this paper saves you time and points you to the raw data.

Source

Original article: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09811-4