An RNA splicing system that excises DNA transposons from animal mRNAs

Article Date: 10 December 2025

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09853-8

Summary

The authors describe a conserved, previously unrecognised RNA-processing pathway they name SOS splicing (Splice-Outside-Splice or SOS). SOS splicing recognises double-stranded RNA formed by inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) — a defining feature of many DNA transposons — and excises those transposon-derived sequences from host mRNAs. The work uses Caenorhabditis elegans genetics and long-read RNA sequencing, reporter assays, a forward genetic screen, proteomics and human cell experiments to show that SOS splicing: (1) efficiently removes DNA transposons from mRNAs in vivo; (2) is triggered by ITR base-pairing (hairpins); (3) requires conserved factors including AKAP-17 (AKAP17A in humans), CAAP-1/CAAP1, MSUT2 and the RNA ligase RTCB; and (4) operates in human cells on reporter transposons (Tc1 and HSMAR2). The TE excision step itself remains mechanistically unresolved, but the ligation of the resulting mRNA fragments depends on RTCB and associated factors localised to nuclear speckles.

Key Points

- SOS splicing excises DNA transposons from host mRNAs in vivo in C. elegans and can operate in human cells on reporter constructs.

- Trigger: ITRs that form dsRNA hairpins are necessary and (when inverted) sufficient to initiate SOS splicing; scrambling the sequence but preserving base-pairing retains activity.

- Core conserved factors: AKAP-17 (AKAP17A), CAAP-1 (CAAP1), MSUT2 and the RNA ligase RTCB are required for efficient SOS splicing; CAAP1 recruits RTCB to AKAP17A in nuclear foci.

- SOS splicing is largely spliceosome-independent (resistant to pladienolide B) and often uses non-GU-AG junctions; the excision nuclease/process is still unknown.

- Biological effect: SOS can restore function to some TE-interrupted genes when splicing yields in-frame mRNAs, but it is imprecise and often leaves indels or out-of-frame products.

- Implications: conserved across species, with potential roles in mitigating transposon damage, regulating RNAs that contain inverted repeats and possibly processing viral or other structured RNAs.

Content Summary

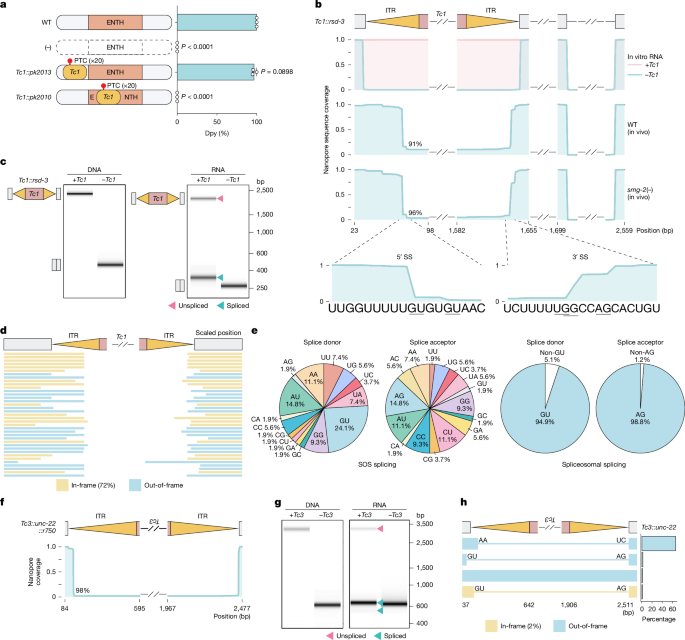

The authors validated SOS splicing by nanopore long-read sequencing and RT–PCR of multiple C. elegans alleles with DNA-transposon insertions (Tc1, Tc3, Tc4) in exons and 3′ UTRs; in all tested exonic cases, the transposon sequence was excised from 90–100% of mRNA reads in vivo. They showed excision occurs at multiple positions near ITRs, often not at canonical GU-AG splice sites, and leaves short indels.

Reporter assays (Tc1::NmScarlet, Tc1::Ngfp) demonstrated in vivo SOS splicing and revealed that deleting ITRs abolishes the response while preserving inverted base-pairing (even with scrambled sequence) maintains activity — pointing to a pattern-recognition mechanism based on RNA structure rather than specific sequence.

A forward genetic screen in C. elegans identified three genes whose loss blocks SOS splicing: C07H6.8 (akap-17), sut-2 (msut2 orthologue) and F15D4.2 (caap-1). AKAP-17 is an RNA-associated protein that binds TE-containing mRNAs (RIP–seq) and localises to nuclei; CAAP-1 bridges AKAP-17 and the RNA ligase RTCB.

In human HEK293T cells, Tc1 and HSMAR2 reporter constructs are also SOS spliced and produce GFP in a fraction of cells; AKAP17A and CAAP1 knockouts abolish reporter rescue, and RTCB depletion reduces SOS efficiency. IP–MS, co-IPs and split-GFP assays place CAAP1, AKAP17A and RTCB together in nuclear speckles, and mutating catalytic residues of RTCB in worms blocks SOS reporter rescue — consistent with RTCB ligating mRNA fragments produced during SOS splicing.

Mechanistically, SOS splicing: (a) is initiated by dsRNA hairpins from inverted repeats; (b) involves excision of the repeat (unknown nuclease or RNA-catalysed chemistry); and (c) depends on RTCB to religate the flanking mRNA. The process can sometimes cooperate with the spliceosome (hybrid splicing) when canonical splice sites are nearby.

Context and relevance

Transposable elements are abundant and can disrupt genes. Classic defence systems silence TE expression, but SOS splicing represents a distinct, post-transcriptional fail-safe that can remove transposon sequences from mRNAs after insertion. The pathway is conserved and uses broadly conserved proteins; that strengthens the argument it is biologically meaningful, not a nematode oddity.

For researchers, SOS splicing opens new lines of enquiry: identifying the nuclease or RNA chemistry that excises TEs; mapping endogenous human targets (TE relics, other inverted repeats, viral RNAs); and exploring whether controlled SOS-like processing could be harnessed therapeutically to remove harmful insertions or engineered sequences from transcripts.

Author style

Punchy: this paper announces a genuine new RNA-processing pathway with conserved machinery and clear functional consequences. If you work on RNA biology, transposons, genome defence or RNA therapeutics, the molecular players (AKAP17A, CAAP1, RTCB) and the structural trigger (ITR hairpins) are worth reading about in detail — this could change how we think about post-insertion gene rescue and RNA repair.

Why should I read this?

Short and blunt: it’s neat — organisms not only silence transposons, they can snip them out of mRNAs. If you’re curious about how cells tolerate genomic parasites or want fresh ideas for RNA-based fixes (or antiviral strategies), this is packed with usable clues and conserved factors you can follow up on.