Laser-based conversion electron Mössbauer spectroscopy of 229ThO2

Article Date: 10 December 2025

Article URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09776-4

Article Image: https://media.springernature.com/lw685/springer-static/image/art%3A10.1038%2Fs41586-025-09776-4/MediaObjects/41586_2025_9776_Fig1_HTML.png

Summary

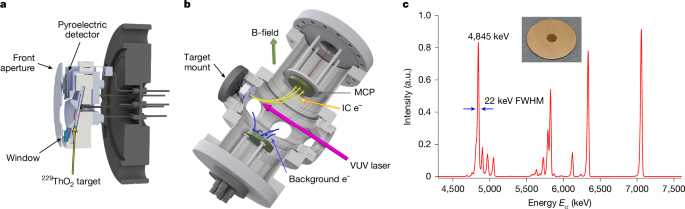

This paper reports the first demonstration of laser-based conversion-electron Mössbauer spectroscopy (CEMS) of a nucleus. A tunable vacuum-ultraviolet (VUV) laser was used to resonantly excite the 229Th nuclear isomer in a thin thorium dioxide (229ThO2) target (~10 nm). Instead of relying on weak nuclear fluorescence, the team detected emitted internal-conversion (IC) electrons as the nucleus decays, producing a direct CEMS spectrum. They determine the nuclear transition frequency as 2,020,407.5(2)stat(30)sys GHz and measure an IC lifetime of about 12.3(3) μs.

The authors combine the experiment with solid-state theory (DFT and G0W0 + BSE) to calculate ThO2 band structure, projected joint densities of states and estimate internal-conversion rates. Theory gives a bandgap ≈ 6.2 eV and predicts IC lifetimes in the tens of microseconds (order-of-magnitude agreement with experiment after accounting for approximations). They discuss how laser CEMS opens spectroscopy of low-bandgap hosts, enables new materials probes and points to a novel solid-state nuclear clock design with projected instability ∼2×10−18 at 1 s and a simple current-based readout for compact clocks.

Key Points

- First demonstration of laser-based CEMS on any nucleus: VUV laser excitation of 229Th in a 229ThO2 thin-film and detection of emitted IC electrons.

- Measured nuclear transition frequency: 2,020,407.5(2)stat(30)sys GHz; measured linewidth consistent with laser bandwidth.

- IC lifetime measured ≈ 12.3(3) μs; theoretical estimates (DFT + many-body corrections) give lifetimes in the tens of μs after correcting approximations.

- ThO2 has a computed fundamental bandgap ≈ 6.20 eV (G0W0), consistent with prior measurements; only near-surface 10 nm depth contributes effectively to IC electron extraction.

- Experimental design mitigated VUV-induced photoelectron background using timed bias switching, spatial/electric/magnetic electron focusing and ASE quenching in the Xe four-wave-mixing source.

- Laser CEMS extends nuclear spectroscopy to low-bandgap hosts (previously excluded because radiative fluorescence is quenched by IC), enabling new probes of local electronic, phononic and chemical environments.

- Potential application: a conversion-electron nuclear clock with much faster interrogation (IC decay ~108× faster than radiative decay) and projected instability ≈2×10−18 at 1 s, with possible simple current-based readout (~300 nA).

Context and relevance

After decades of effort to access the laser-addressable 229Th nuclear transition, recent laser excitations in high-bandgap crystals unlocked nuclear-clock research. This work pushes the frontier by demonstrating detection via conversion electrons, removing the strict need for very large bandgap hosts. That means researchers can implant 229Th into many more materials and use the nuclear isomer as a probe of local chemistry, strain and phonons. For atomic- and nuclear-clock communities, the faster IC channel opens routes to dramatically shorter interrogation cycles and simpler, potentially miniaturised solid-state nuclear clocks. The combined experimental–theoretical approach also sets groundwork for quantifying host-dependent frequency offsets and for engineering materials (including defect or band-structure engineering) to tailor clock performance.

Why should I read this?

Short answer: because they got a nucleus to cough up electrons on demand. Long answer: if you care about ultra-precise clocks, new quantum sensors or novel materials probes, this is a milestone — laser CEMS lets you study 229Th in materials that were off-limits before and points to tiny, fast nuclear clocks with current readouts. It’s a big leap and saves you digging through a lot of dense methods: they’ve done the tricky experiment, nailed a frequency and measured the IC lifetime.

Author style (punchy)

This is a landmark, not a footnote. The team demonstrates a new spectroscopy platform that immediately broadens the range of solid hosts for the 229Th nuclear transition and directly feeds designs for radically faster, simpler nuclear clocks. If you follow metrology, quantum sensing or actinide materials, the experimental choices, the mitigation of VUV backgrounds and the agreement between experiment and corrected theory are all highly relevant — read the Methods and theory sections if you want to reproduce or adapt the technique.